Holy moly! There are only four chapters left of B.C.Y.: A Novel. Next time, we will present you with a new working title to see how that fits. If you like it, tell me what you think. Episode #8 of B.C.Y.:A Novel is ready and waiting for you below. As I’ve said before, read from the beginning or start with Chapter 8. If you read from the novel's start, you’ll get to see the story's arc and the main character’s episodic journey, like our old pal, Picaro, Voltaire’s Candide, or one of my very favorites, Ellison’s Invisible Man. But feel free to jump in wherever you want.

Preface: This is a serialization of B.C.Y.: A Novel (working title). If you missed the earlier Chapters, you can find them here: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, and Chapter 7.

Chapter 8

So, the second half of junior year was a little better than the first. Taking a course from the son of the great Bertrand Russell was an honor. Conrad Russell looked so much like the photos of his famous philosopher father, although I had never read anything by either of the Russells. It was the gravitas in the picture around their mouths and the hairlines. Russell the Younger taught a course on Stuart and Tudor England, both subjects I knew absolutely nothing about.

My desire to dive down into something that I would find authentically myself was thwarted by a kind of regression. I thought that it was time to become a professional actor. I’m not entirely sure what this was spurred on by other than the fact I didn’t have enough to do in my courses and in the rest of my life. That last thought was not even funny to me, but failure always spurred me to dig in, try harder, and do more. Whenever I overextended myself, I always came out on top. High School. Freshmen year, sort of. Maybe I could ward off failure – a whole lifetime of Fs – by doing more, less well. Schaeff-y Pretzel Logic. Or, the Old Twenty-three Skidoo.

It all began innocently enough. One of my classmates' mothers was a manager, and she wanted to represent a few of us with one agent in New York. I’m not quite sure why I was chosen. If she had dug down a little deeper into my recent background, she would have seen how I never was good at finishing stuff, mainly stuff that I cared for or about which I was too afraid to put myself out there.

We met at a coffee shop breakfast place that served organic muffins. This was not my choice, but who was I to spit into the windy wind?

“So tell me, what really gets you going?” Jan, the manager, gushed a bit.

“I mean, like in acting?”

“No, in life. What makes you get up and out of bed?”

“I mean, I don’t. At least, I mean…” Why was I so inarticulate? “I guess my first-period class…”

“You look like a young Levar Burton.”

I visibly cringed at the notion of being Kunte Kinte.

“Like in…”

“Roots,” she finished my thought and kept’em coming. “Just like in Roots.”

I was used to people mistaking me for a lot of people, but a slave was not one of them. Yet, she read the disappointment or lemon-tasting look on my mouth.

“I did not mean to… Heaven, forfend! I am so sorry.” She backpedaled. “You just have his…”

I shrugged as if I wanted to be anywhere but here.

“That expressiveness around the eyes.”

After I ate my zucchini-nut muffin, I thanked Jan for the hour and a half of getting excited and disappointed all at the same time. What the hell was I getting myself into?

“Thank you,” I mouthed. And almost under my breath, “Count me in…”

So that’s how it all began. How I would Hopalong Cassidy to “Completion.” More obstacles along the course.

The agent we were hooked up with was someone who primarily dealt with child actors and young adults. I would often daydream when I would get my actual adult card. The gift of my own genes was that I looked all of fifteen when compared to my scruff-beard-growing classmates. I didn’t even start shaving, even a little, until that year.

“Hey, weirdo, what are you looking at?” Ethan flopped out of the shower, seeing that I was waiting for him to get out – the dude had hair everywhere, even starting to grow on his ears. I eyed him curiously as if he were a painting in a gallery, looking at the angles and contours of his face. We were both primarily nonverbal in the mornings until we got that first cup of joe in the dining hall. He pushed past me as I wrapped up brushing my teeth, waiting for this opportunity to learn something I had been thinking about for months.

“You know, you’re freaking me out, Bozo!” As he went through his usual routine of beginning the process of exfoliation under my spotlight of an examination.

“I bought a razor and shaving creme down at Wawa’s. I’m looking for a few pointers on, you know, scraping the face.” I had my razor out now and a baby-sized version of the knock-off shaving gel, Bar-Beez.

“What am I, your Dad or something? Get out of here!” Draped with a checkered towel over the bottom half of his body, chest hair making a small rug-size hair-swatch across his abdomen, he got both of our attention by letting out a gargantuan fart.

“Hey, you talking to me?” He De Niro-ed himself over to the other sink, turning on the spigot. Tooting loudly again, “That’s what I think of you and your shaving if you really want to know.”

He wasn’t even looking over in my direction, but we could hang with each other in this way. We’d sometimes even talk to each other as we sat in the stalls taking a dump. I had watched him shave dozens of times, but this time, I needed to figure it out for my own face.

As he ran the water until it got scalding hot, he dunked his face with water over and over, performing some purification ritual like his other Abrahamic brothers might, so it became tacky and moist, slaking his face with the hot water to get it to the correct absorbency so that he could work it like raw clay. Even in the kneading, scraping, contour following, and hand-building, he began sculpting a new person. Ethan did this each morning, every damned day; he was, day by day, putting himself together like Humpty Dumpty.

In every way, I did the exact same with mine, drawing a long gleek of blood with the cheap-o Wawa knock-off brand razor, turning the shaving creme of my face to a mottled pinkish-red. I only had a little fuzz on my upper lip but nothing at all around my neck or the lower half of my face. I wouldn’t really for years.

For Ethan, by one or two o’clock in the afternoon, the artless, rough-hewn texture of his pre-shaved face would return. Hairs would have already started to sprout again, returning to bone dry and ready to start the process all over again the next day. He could have shaved at least twice a day. I would eventually go every two to three months between shaves.

Our worlds were different, like the preparation of our two faces each day. He would do all those mental gyrations to prepare to attack the day while I was thinking of becoming something entirely different than my classmates, something less formed, as I began to think about leaving at the end of my time with these people and this place. I had no idea of how I might get there.

I would sometimes start to get calls for auditions in THE City. Getting ready to navigate the New York acting scene meant I had one more distraction that I gave myself towards finding what I really wanted to do post-college. Usually, after I had navigated a terrible audition for a pre-Broadway show that nobody ever heard about, I would meander up to 57th Street past Carnegie Hall to my agent’s office on the 21st Floor.

Roda: Hey, Schaeff. How you doin’? How things up there in No Haven (laugh).

Me: Can’t complain. How ‘bout you?

Roda: It’s a bucket of love-monkeys around here with all of the Olivers and Annies raomin around. How’d it go over at Walt Hamilton’s Casting?

Me: They were cool, but they stopped me mid…

Roda: Oh, Shaver… I mean Shaeffer, you gotta do better at preparin’. What they teaching you up there?! You taking any thee-ayter acting classes?

(a beat)

Roda: Oh, I forgot. Sorry… Go get’em next time. Okay?

Me: Absolutely. Next time…

That was the extent of my first two years of being agented. Something that most actors would give their eye-teeth to get. I’m not even sure what an eye-tooth is, but I had an agent and supposedly a good look for commercials and TV, but I couldn’t buy a job. I would hobo-it back to Grand Central to take the Metro North to the friendly confines of New Haven’s Union Station, usually pretty defeated. I needed that non-apocalyptic groove, but all I could muster was more doom and gloom.

Many of my classmates were headed for the hills, marching inexorably to law school, med school, business school, or financial stuff. I even heard tell that the FBI and CIA were recruiting on campus, probably those secret society dudes, which certainly was not going to be me.

A few of my comrades, like Ethan, were already planning to take a year off to travel the world. That was old Ivy League, where you would do a walkabout. North Africa was on a great many people’s lists. I, for one, had no idea what I would do after school, but I knew that acting professionally would probably be a part of the plan. Maybe other people would go work on their tans. I had no idea because nobody I knew wanted to discuss it too deeply, at least not with me, they didn’t. We were still just diving into each other; relationships seemed to get more serious, and we headed into the conjugal territory, or we dove into the classes in our major that seemed to interest us.

During this time of examining American history and letters pretty closely, with a foray into pre-Windsor England and Brazilian history, I figured I had had it with academe. It didn’t seem like it suited me, nor did I suit it. Again, as was my M.O., I had fallen out of love with love.

College changed fairly significantly during this time due to the advent of the personal computer. The more advanced students like my buddy Chris had invested in a big and clunky Kaypro computer somewhere during his sophomore year. It was like something the army would use to communicate with the troops deep inside some jungle or other. I remember our pizza bones-eating buddy Chris tick-tacking away while the rest of us had manual typewriters or even a time-saving Selectric here and there, which was advanced stuff for a college dorm. The hum of a typewriter and the clack-clack-clackity-clack across the campus was kind of soothing when you passed somebodies dorm room or even when you heard that sound out of the second-story window as you passed someone on the European-faux flagstone pathways.

I would hear people in the wee morning hours finishing up on papers and projects, which meant that you had to be cogent and careful to be precise. In my mind’s eye, everyone produced flawless masterpieces of prose that went from their head — like thoughts from Zeus — onto the page. But in reality, many of those papers were fine glue-sniffing, high-inducing messes of mistakes and a Picasso-worthy criss-cross of Whiteout that dotted across the page. Couple that with the handwritten mistakes after the editing was done, and you would get something you wouldn’t want your worst neighbor to read. At least, that was true from my own writing during those years.

I took a good many of these courses WI, or writing intensive. I knew that I was behind on my writing and even worse on my editing. I needed to spend the time reading and writing more than anyone else. I remember a few of the papers that were written. I do remember one exam where I had a grand time writing about Wieland and “Young Goodman Brown,” which sounded a lot like a Black soul quartet.

One Blue Book essay on Wieland I did remember the gist of, which went something like this:

Charles Brockden Brown could have been living inside of my own head last year. As Wieldand descends into madness, plying his serrated view of the world to try to cut the noises he heard from the disembodied voices in his home. It stands to reason why people should not spend excessive amounts of time in their head and alone. Like Wieland, the title character of arguably America’s first home-grown Gothic novel, you could go off your cookies, like someone close to me I know did last year, who left indelible pieces of himself, and I’m not talking about his visage, all over town, ending up insane and alone, with loved ones trying to piece him back together again.

That essay wasn’t too shabby, considering the mediocrity that preceded it. I got a B+ on that mid-term and later a gentleman’s B in the course, even though the rest of my junior journey was uneven, spanning the range of C- to B+. I did get an A in a film class where I was the helper-dude, but being the AV guy in that class was like watching Halley’s Comet come back one more time.

So, between the classes and the newfound sense of freedom, heading into New York, I was stretched way too thin. In April, I began traveling even more back and forth on the Metro North to Manhattan to audition for various projects—commercials, Soap Operas, TV series, and another pre-Broadway legit play. I was also caught psychically somewhere in the middle. That’s the whole problem with being betwixt and between. It was somewhere in the back of my mind that I might be under-prepared for any kind of work that came my way because I had not consistently acted since high school. However, since I had not thrown it over in my mind to focus on the tasks associated with finishing up college and becoming a real working actor, I wasn’t proficient or even basic at anything. Unoriginal and uninspired, is what my professors might say. I was at war with myself, and it was taking a toll on my energy. I was told by this one casting lady that I had the looks of a viable actor but the work ethic of a spoiled rich kid, and this was coming from someone who had a successful kid in the business who was used to playing spoiled rich kids, so she should know, right? As I proceeded to go to New York a few times a month, I had the idea that I was ready to make money at it.

One of the TV movies I auditioned for was Be Not Afraid, about a young man who gets to enroll in one of the New York City colleges but is under-prepared. Very familiar. Getting to the audition and even getting a callback was thrilling. Yet, watching the actor who later got the role come out of the audition smiling, sweating, and huffing and puffing…

Famous Casting Lady (sprinting out through the waiting area to catch up with the soon to be famous young actor who was not me): Hey, Mike. Uhmm, would you mind, you know, waiting just a few minutes until we finish these last two. The uh, producer is coming by and I know she’d want to meet you! (gush)

I could feel my lower lip stick out all on its own, daring me to leave while the leaving was good. So, that was the early efforts of my beginning actor days. No cigars and not even close. It felt like trying to knock all those heavily painted gun-metal-grey bottles down at the carnival with that damned bean bag.

I realized there was a world of difference between what Mike was doing and what I could do, even in the waiting room. I was next to the last one the producer did not want to meet, who stayed to add to my sad humiliation with an early “thank you!”

It was a pretty sad time to be me at this point, drafting off of an older, outdated conception of myself, the one that fewer people remembered, including me, where I was more accomplished than I actually was. Where was the authentic, real version of me, where people didn’t need Cliff’s Notes to figure me out?! I wanted to be committed like Mike. He lived the role. Perhaps trying to do everything was a fool’s errand. I felt less anxious these days but still not rooted to anything. I could never imagine being that committed to something, living that fully and that deeply to something, that you came out panting and huffing and puffing. That was some Robert De Niro kind of smack right there.

De Niro was the gold standard. Ever since Taxi Driver, a movie that had certainly already changed one of my classmates’ life and career, was there ever a man so on point with who he was playing and what he wanted in a scene? During that hazy sophomore year and with the advent of cable in the TV room in the steam tunnels, I must have watched Raging Bull thirty times. It was a lesson in losing yourself in a role. Watching the movie over and over starkly reminded me of what I wanted to do with my life. And, would it hurry up so that we could get there fast? The lesson in all of this was staring me right in the face. It was to do school, not just to complete it. There was a shallowness about everything I touched, which could not be articulated at the time but was lived. Perhaps that is the essence of a kind of half-life. Not the half-life of plutonium, but a kind of second life that only actors and politicians seem to get.

De Niro mattered because he was the beacon of what it looked like to commit, to gain forty or fifty pounds. Gee, that must have been fun to get to that point, to learn to look like a boxer and be absolutely committed to playing a real-life person like Jake LaMotta, and to be original. Raging Bull and De Niro’s performance screamed BE ORIGINAL.

Why wasn’t this lesson happening in the classroom? Perhaps it was, but I don’t remember much of my own original thinking or scholarship coming out in those days. It felt like what the old folks at home called Half-stepping. Half-stepping meant that you weren’t really all that into what you were doing, that you could have done better, and you could have done more. It’s hard to do better and to do more when your world is split between being on the train and being in classes. Wasn’t I doing more already? Where was that mentor when you needed her or him? Wasn’t that what being in a place like Yale was all about? The vastness of all of those erudite adults and peers. Vast like the ocean. Water, water everywhere, but not a drop to drink.

The lesson in all of this has to be in what a person perceives as authentically his or hers. What value will it take to wrestle that degree of authenticity to subdue it, to have it cry uncle, and to say that once and for all, you are the greatest who ever lived?

Getting back to school, I took over the Pierson Cabaret. I needed some sort of creative outlet that wasn’t about beating myself up with work. If I just put my head down and devoted my energies to just a couple of things, maybe those things would be good, and just maybe it would be worthy of my time.

The Pierson Cabaret was a talent cavalcade of people from around the college who wanted to perform at something they loved. Maybe a person was a good vibraphonist, or perhaps they sang like no one’s business, whatever it was, we would put them on the shows stage and invite people to come in to see them. There were a great many jazz singers. Many folks from the various a cappella groups would want to try something solo, but they would bring their group members, girlfriends, or boyfriends in to support their efforts. I loved putting on a show every few months, inviting a few other people in to help, doing the lighting or soundboard, and decorating or designing the poster in the Pierson printing press. In addition to corralling the acts, my favorite job was working the staple gun and hanging the posters all around the campus and even in different parts of New Haven, which was quite something.

The daytime was for more philosophical musings and debates in the dining hall. It was not business as usual. I tried to understand what made my time at college so special. It was all of the stuff that was learned in the dining halls. One Friday afternoon late in the trimester I remember sitting with a small group of friends talking with the Master of the College who I had to remember most times that he also was an M.D. who worked up at Yale-New Haven Hospital. The topic somehow turned to plagues. The visitor, an Englishman in his late thirties, I imagine, began talking about a new plague, one that was sweeping the gay communities around the world, particularly in New York and San Francisco. He called it human immunodeficiency syndrome, where the body attacks itself, and the blood begins to attack its own body, causing a number of wretched complications. The worst of it was the complications of those attacks called pneumocystis pneumonia, where your lungs fill up with fluid, and you die. The Englishman said this could very well be our plague. It was gruesome shit.

“You died because you loved someone?!”

That was a thought that pushed me even further into my own aloneness and one I could not shake. Already, with the lack of closeness and intimacy that seemed to abound within the small circle of friends I had, it was now possible to find that love and still end up alone or dead. The carefully crafted image I had created was one of being a player, but in reality, I wasn’t. I was just as solitary as most, with a carefully curated reputation of not being that – for protection.

In the same dining hall where we heard “Lady Be Good” or “Can’t Help Loving Dat Man,” we also heard about far-off revolutions and the scourge that would kill a number of talented men and women of our generation. That it was their very passions that would take their lives from them. It gave all of us pause to think through the ramifications of being young and to have the world so different than it was during our own parents’ generation. The work for all of us was to stay conscious and vigilant and try to look out for each other just a little bit better than before.

Classes and the New York City excursions took on a different hue that spring. Early in the morning, after pulling an all-nighter up in the Pierson Library, I was the last one left, trying to read the two texts I was using to prepare for one of my Stuart England papers. It just wasn’t coming. Not only was it not coming, but it was getting nigh towards the end of the semester before finals week.

At these times, I learned that my baby-bird systems of organization and study were fragile, probably more fragile because of the way I was abusing my own body with the lack of sleep. There wasn’t much of a way around it. I was behind, and I had to get caught up. Stuart England wasn’t the only paper that needed my attention. There was also a paper and oral report in front of the entire class on Brazilian history and a few other projects that were left until the very last minute.

One early morning in late April, as I was finishing up my reading, I realized that I had been up for about forty-two hours straight. I wasn’t taking in any of the words I was reading; I was just scanning the lines. I fueled myself on cups and cups of tea to the point that I was running to the bathroom every twenty to thirty minutes, and I had a tremor in my hand that was shaking my reading material to the point that I couldn’t read it. Because my brain had shut down, I didn’t realize what was happening. The shaking worsened to the point that my chest began to convulse. Unlike the years before, which was a bit of a crack-up moment, this new time was mainly about just trying to go to sleep. The problem with going to sleep was that I was way too caffeinated to fall asleep, and my heart was pounding like a bass drum at Mardi Gras the way it was. I did the only thing that I could do at that point.

I walked across the quad, opened my door, went to my room, pulled off all my clothes, lay down under my covers, and waited for sleep to take me in the early morning hours. Whatever I had going on during the rest of the day would have to wait. I had an audition later in the afternoon in New York for a new sitcom that I would not go to. It had to wait. My life was on hold, and the old mantra came up: completion. Yet, something else also rose at the same time, which was, ‘You can do better than this.’ It was true. I could do better, but would I be able to learn that lesson in time? Would I be able to tame my own thoughts about not doing well to do better? I certainly hoped that I could. There wasn’t much going back.

I woke up minus the creative energy of dreaming I once had or without the ability to remember my dreams. Sleep was like the fuzz at the end of the AM dial. In fact, this entire year had been monochromatic, like a stream of consciousness and a stream of words rooting around in my head, looking for a place to sprout. With ten minutes to spare before dinner, I had gone to sleep exactly twelve hours earlier at 6:50 AM. This was certainly no way to live and to study. College was beginning to feel a lot like a POW camp, but I was my own captive and captor – in solitary confinement.

There didn’t seem to be much that I could do to get off this treadmill, but I was resigned to “win” whatever that meant. I wouldn’t have anyone else to blame for my failure, not Yale, my pining for home, or ill-preparedness. There were Black students who had hustled through this place or were currently doing so, like Rosey Thompson. As I heard it, he was a football player and one of the best and brightest in our class. Indeed, there were people doing extraordinary stuff coming from places in even more dire need than from where I came. I heard that Rosey would be working for a new young governor in the State of Arkansas, and perhaps Rosey’s future would be that bright, too.

To be honest, I didn’t know the brother. I do not believe our paths had crossed even once. Maybe we gave each other the Black man nod crossing campus, but Yale was a sea of loose connections, like a hall light that flickers when you turn it on. Yet, I didn’t necessarily have any or many role models that I could lean upon, someone who could coax and coach me through the bleaker times.

With just a couple of minutes to spare in Pierson Dining Hall, I grabbed a couple of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. I had to cut the bread myself from the thick kind that the dining hall staff made themselves. I would much rather have store-bought wheat bread, but beggars can’t be choosers. I pieced together four slices of bread. When I took the sharp, serrated knife in my right hand, I saw that it was still shaking uncontrollably. I did the deed of slicing the bread, like the main dude from the Scottish play, but I would try to lay off the caffeine for now until I could gain my footing again.

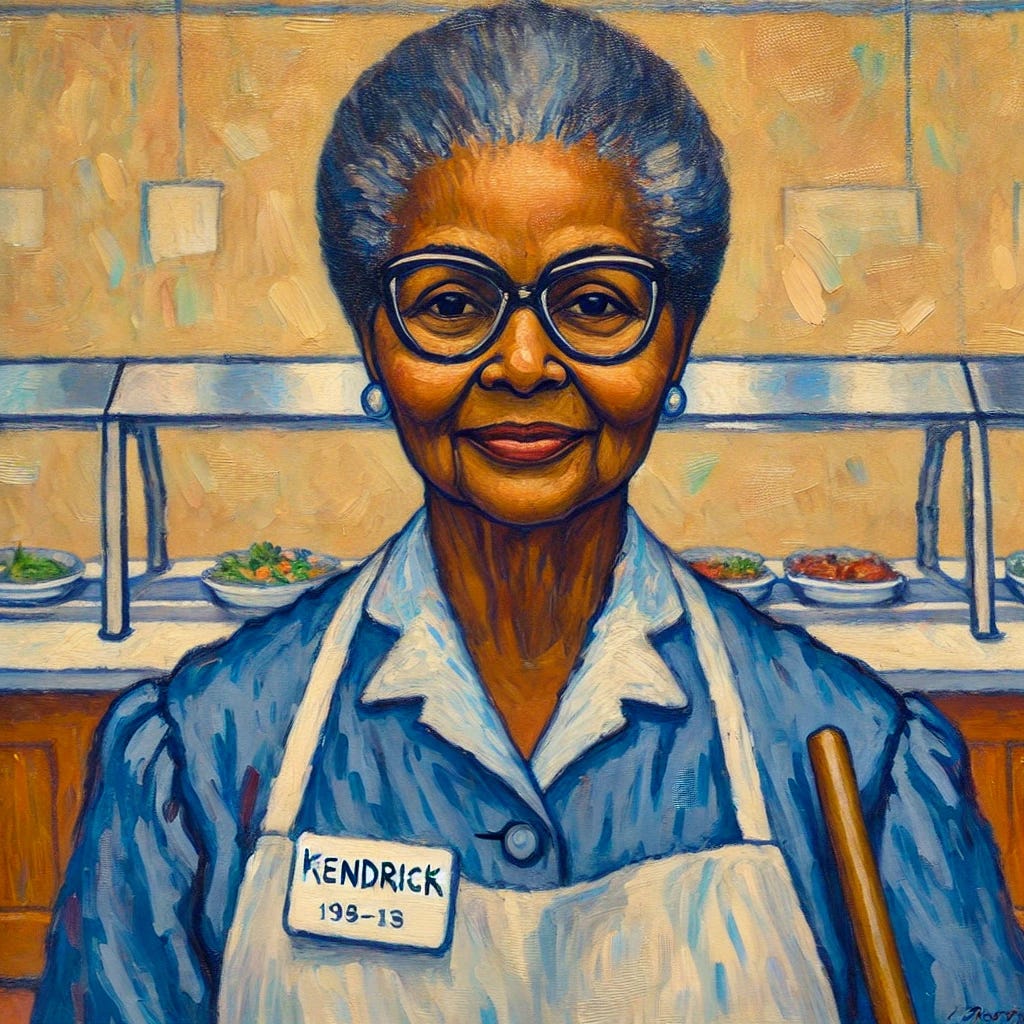

Over in the corner, I could see one of the dining hall workers as she began to wipe down the tables and clean up from the day. She was this slight of a build Black woman, maybe a skosh smaller and younger than Mymama. She lived down Dixwell Avenue with her family. She invited me to her house for Thanksgiving dinner when I was a sophomore when I couldn’t make it back home that November. I hadn’t seen her in a long while. It took me a few minutes for me to scan back through my overloaded memory bank to remember Mrs. Kendrick’s name. I tore off three even paper towels to wrap my sandwiches up at the bread bar. I made my way over the the corner of the room where Mrs. Kendrick was deep into her routine.

“Hi, Mrs. Kendick.” I wanted to convey how much she meant to me and also apologize for not following up with her all this year. She was very sweet to me.

“Hello, young man. How are you doing?”

“Oh, you know, Mrs. Kendricks, whatever don’t kill you…”

She laughed at this. I saw that she had slowed quite a bit during the time that I last saw her. She told me that she had rheumatoid arthritis, and her hand was beginning to show the buckles and knots that the condition had on people.

“Oooooo, Schaeffer, your hair is getting long. You should come on by our house this weekend so that I can get Clifford to cut it.” Clifford was Mrs. Kendrick’s youngest son. He was my age, and he was finishing up at barber college when I met him last year. He had a very nice yellow Camaro that he took great pride in.

“I’d love to do that, Mrs. Kendrick, but I am so behind with work. I hate to tell you this, but I just got up about fifteen minutes ago.”

“Ooooweee, Schaeffer. You work real hard. I know yo’ Mama is very proud of you. You know, we become writin’ friends. She write me. I write her. ‘Bout every mont’ or every’other mont’.”

“I did not know that. It figures. My Mama’s good about writing.” With that, I got a wave of nostalgia and regret. I could see Mama at our dining room table in the chairs and the formal dining room she was the most proud of in that house. Dark, deep wood that we polished with Olde English oil when we first got there and probably never touched again after that. I pictured King, our German shepherd, lying down on the rug between the living room and dining room. It wasn’t that big of a room, either of them. The whole house was a boxy rectangle, with the dining room being sandwiched between the kitchen and the living room. There were a few rectangular rugs on the hardwood floor that warmed them up. They would become a tripping hazard for my grandmother in the next few years as she came over and stayed more and more.

When I thought of my mother writing to Mrs. Kendrick, I thought of all of the people I would be letting down if I didn’t finish. It didn’t matter that I wasn’t Rosey Thompson to them; they just wanted to be able to say that I was a college grad. I know that was important to those women when I was in first through fourth grade in schools in Robbins at Lincoln and Berneice Childs School. They went to Tugaloo State, Tennessee State, or Jackson State. They knew what their futures held for them. Most of them got married, but they were the pride of the town for coming back and giving back. Those women, which could have been Mrs. Kendrick, were the ones I should be thinking about to get me through.

I could see that Mrs. Kendrick was watching me think about all of this stuff as my eyes filled up with tears.

“Just come on by. I hear that apple pie is your favorite. I’ll make one of those for you.”

I wiped back some tears that were beginning to stream down my cheeks, pooling beneath my chin, “I will take a rain check this time. I have so much to do, but I can’t tell you how much this...” Unable to speak any further, I gestured back and forth between her and me. Fighting through, “You mean… so much to a lot of us. I just want you to know that.”

With that, I grabbed my sandwiches so tight between my fit of emotions and tears that jelly oozed off the bread and napkins, staining my shoes. I didn’t care. I got a hit of self-worth and guilt and climbed back up the stairs to my room.

I would work intermittently throughout the evening. It was important that I attack all of these classes in some sort of orderly fashion. I was behind, and I needed to think through all of these interactions that I was having while wanting to shove them into the overstuffed closet of my mind. The exchange with Mrs. Kendrick made me acutely aware of what was at stake. It was not just about me. It was about a generation of women like my grandmother, my mother, my aunts, my cousins, and all of those Black teachers who devoted so much of their time and energy to ungrateful young men and women like me, who never came back to thank them for their courage to teach us against the odds. They were assigned an impossible task most folks would have failed, but they weren’t given the credit for holding a vision for those of us who would achieve good things. Perhaps they weren’t the most lofty of accomplishments, but at least we were productive, and they might hear about us in the grocery stores when our mothers came through and stopped them in the store.

They would be checking out or just coming in near the fresh vegetables and fruits.

“How is my boy up there? Where is he at?” Not at all worrying about the preposition this time.

“He still up there, in Connecticut.”

“That is something. I am so proud of him. We are so proud of him. All of us.”

Our mothers would be there, talking about how long it had been. Hadn’t it been such a long, long time? Perhaps the teacher wouldn’t quite remember the name of the mother, but she would remember that it was the mother of one of her former students, someone who was doing well. Or, so it seemed on the surface.

They would talk as if they both were unaware of this not-knowing-names thing. Then, with enough context clues, the teacher would get it. She would slip in, “How is Mylie and that Schaeffer really doing? How are both of them boys?”

Mama would regale them about Yale, Northwestern, and medical school in that order. The teacher would say, “I’m so glad, Baby. I could just about bust.”

These women taught my father, my uncles, and my aunts. They knew them well and remembered them all well, even if the names wouldn’t always come easily. These teachers knew that progress came incrementally, not like a bolt of lightning. It came when it came. Sometimes, when it didn’t come, you just had to be patient. Then it would come. We were progress to my teachers and our mothers, to our little village and the bigger city to which we moved. They represented what was good and true about growing up where we grew up. Growing up with no excuses or hard feelings or excessive worries.

All of these memories flooded back to me as I studied in my dorm room, in the stacks at Sterling Library, at CCL, and in the Pierson Library. I just knew that if I showed up then good things might just happen. I showed up every single day.

That junior year and the summer after were probably the most formative. Although I had not much memory of the particulars, like the other years, and I still couldn’t concentrate worth a damn, I had moved up and progressed slightly. One day better every day, I would say. Just one day better. After that encounter with Mrs. Kendrick, I did dive down a little bit deeper in some areas. I got decent grades, but I also received at the end of the year another F. This time in Conrad Russell’s class. I never finished the final paper. I’m sure I was close, but it never got done.

[The next Chapter of B.C.Y.: A Novel drops on February 21, 2025, in two weeks, which is serialized at ANEW every other Friday. Spread the word and (re-)read from the beginning: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, and Chapter 7. Tell a friend. Drink some water. Take your meds. Pet a dog. See you soon.]