If something you did years ago has no record—no photos, no saved script, no participants besides yourself—does it exist?

That’s what I’ve been grappling with, writing about a time more than thirty-five years past. In the land of memory, the mind plays its tricks. That was 1990. Imagine: Thirty-five years before seemed like an eternity then, and even more great-grandfatherly now? 1955. The math keeps me honest. But the memory—what sticks—is less arithmetic, more alchemy. Certain moments shine through as pristine, emotionally intact. And within them, the scaffolding of what I believed, who I was becoming, and the values I was forming reveal themselves. Sometimes it's not the event I remember—it’s the feeling, the shape of the moment, the way it pressed against me.

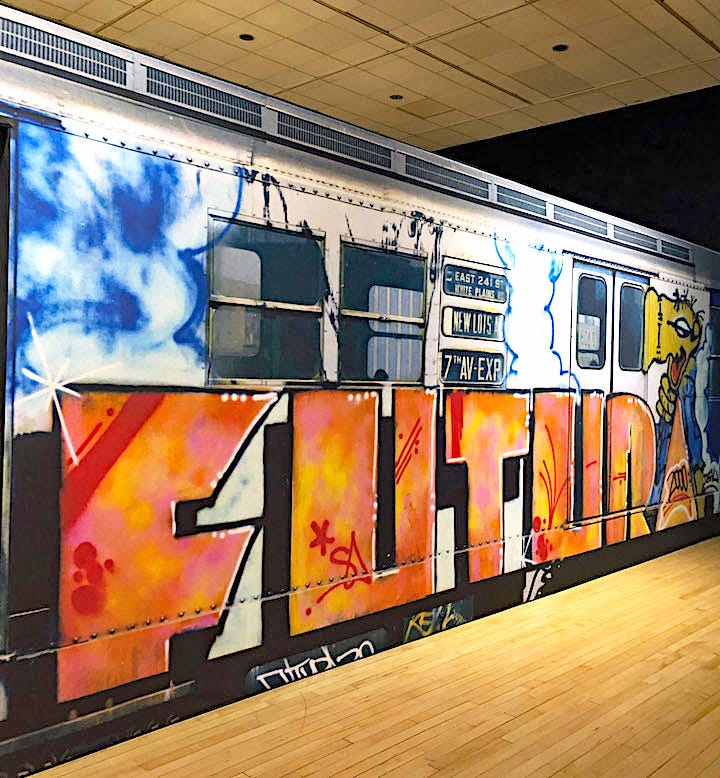

Check it: I don’t actually remember the first time I met Leonard. It was probably at the first table read of Mark Handley’s play MOEEXV (pronounced “MOE-X-15”), a gritty two-hander about graffiti artists—one young, the other younger—writing on the trains in the early days of New York City’s Hip Hop movement. (Yes, there was a third actor — an older white dude, a rent-a-cop, a security guard — but he was no more than set decoration.) Handley also wrote the play Idioglossia, which is the basis of Jodie Foster’s movie Nell, keeping it all in the family.

That’s right: before hip hop was beats and bars, it was tags on trains. The graffiti artists were the original “writers.” That’s what they were called back then. I played the older-younger writer named X-15—X for short—after the record-breaking military jet from his childhood, sleek, volatile, unstable. Like the character. Like the times.

Of course, that wasn’t his government name. It was the name he tagged across the city’s arteries. Leonard played MOE, the up-and-comer. More innocent, maybe. Hungrier, definitely. If X, 20 years old and past his prime, was already a legend in the underworld of transit graffiti, MOE was coming fast. They were boys, really. But the play let them stand in for a generational dance we all know: the moment the student becomes the master, the new eclipses the now. Think Warhol and Basquiat—but in the boneyards, or the places where the subway trains rested at night.

MOE-X-15 wasn’t just about graffiti. It was about being seen, being known, being remembered—by any means necessary, in a world that didn’t see you otherwise. The trains were billboards. The names were claims.

Leonard and I put in work. Deep character study. Reading. Walking the streets. Getting the rhythm right. I had steady gigs—subbing at L.A. private schools, doing group home shifts—but I practically lived on the edge, drifting between Hollywood and Manhattan to breathe in the sounds, the weight, the truth of our characters.

The Malcolm X movie was near dropping in 1992, the X hats were everywhere, and that mattered too. My character’s name—X—carried its own echo. And MOE? He wasn’t supposed to be afraid of X. X wasn’t supposed to see what MOE truly was: a better artist, a rising one. Leonard and I barely spoke in those early workshop days—intentionally. We kept the distance the characters needed. But we became fast friends during and somewhat after the production ended.

After writing this, I did a search—Googled our stage names: Leonard P. Salazar and Brian Wesley Thomas. An old L.A. Times blurb surfaced. Just a brief mention, but there we were.

Then I found something harder: Leonard died of a heart attack, not even living to see forty-five. I loved this line from his obit: “Kids took to him like candy bars.”

I sat with that. While we were working and fully in production, I took to Leonard like the best dude I ever met. And he was.

How fragile it all is—how fragile we’ve always been. It’s wild, really. We’re out here spinning art into the void. Trying to matter. Hoping someone sees. At the Burbage Theater in West L.A., we had a few packed nights—forty, forty-five people sometimes. Other times, and mostly, we performed for a handful, and even some nights for two or three. The smaller crowds were humbling. When the actors nearly outnumbered the audience, those were the toughest. It tests you.

Memory builds the worlds we live in. I sometimes ache with the realization that I’ll never see Leonard again—not here. I won’t get to say, “Hey, remember that time…” or “Remember when we…”

We were so young.

So very young.

So very, very young.

Curated Listening:

Here’s a song that I bet you Leonard would sing to his friends, family, and girls in his melodic voice. Listen to Bob Dylan’s “Shelter from the Storm” HERE. Rest well forever, LPS.