Down in the United States South, there is a collective of artists called Souls Grown Deep. The rap on them says that they are self-taught. It presupposes that certain traditions are not schooled comprehensibly to “outsiders” as if they were in the “academy” or other so-called formal systems of school and schooling. But in our hearts, we know that probably is not the case. As in any tradition, the souls we speak about have been nurtured and supported by those who came before them. In some traditions, such as in many Indigenous tribes, like the Lakota in South Dakota, they say, “Mitakuye Oyasin” or “all my relatives” to indicate this unbreakable bond. In contrast, in others, like African and African American ways, we may call these readily seen and unseen influences “the ancestors.” In these traditions, people who hold to ancient wisdom can sometimes tell you how far back they go, even contradicting narratives or migrations, movements, ice flows, and land bridges, which may be significantly different than the theories espoused by commonly held outside (of the culture) experts who “study” these traditions by looking at pot shards, burial mounds, and relics (i.e., the skeletons of the deceased) to try to make “educated” guesses about what happened to certain people by extrapolating about those remnants “found.” The very act of picking up the shard or removing the arrowhead displaces and confuses those who made purposeful gifts for a future loved one to find. This idea connects us to the past.

I have been thinking about my own deep souls in our family. Last week, I remembered my own father’s passing into the realm of the ancestors six days before 9/11/2001. Although he was not always present with my brother and me, we still felt his presence – his wisdom, his looks, his ways of being and seeing the world, and even his sneeze. What has me thinking about our father now and the other ancestors who have made their way in this world and on to the next is that one of his sisters passed away last week. I spoke with my aunt Sharon – my dad’s baby sister – who I had not spoken to for over twenty years if not more. It was Aunt Sharon who asked me, “Did you hear?” She wanted to know if I had heard from my stepmother Ola that my father’s sister Jeanette had made her journey, usually signaling that she was out of the pain and the loss of memory that ultimately dimmed that light.

Of course, I had not heard. Ola was remembering our father // her husband, locked in her grief, too. When we spoke, Ola, who we called by her actual name to not confuse us boys growing up, was tearful. I did not quite know why she was so doubly bereft until my aunt called. Yet, I did understand that these remembrance days must hit her particularly hard. She was widowed in her early fifties like so many other women in America. The average age of widows in the US is 59 years old. What I know is that there are a lot of lonely folks out there, in many communities that are calling on the ancestors and all their relatives for some hint of what may be next for them.

Ola was lost in the memory of her own aloneness,. Having lost my father 23 years to the day. She cried and cried, wondering who would ever love her like my father had. Her speech was halting, transfigured by a stroke that she had thirteen years before. I told her that she was fine, everything would be fine. That my brother Michael and I were always there for her.

Was I being truthful? Would she be fine? Did we know that things would be okay? Did we understand the depth of the loneliness that a person feels when they have lost or are losing everyone around them and can’t see what’s on the other side for them?

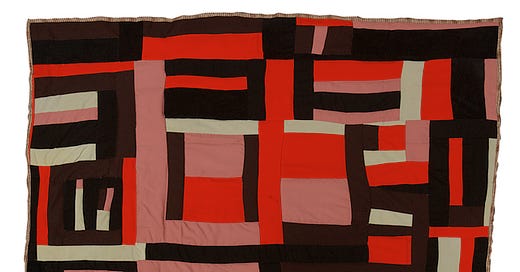

Perhaps this is where the artists' collective can be helpful. Calling on all of those souls who have gone before, even talking to them as you once had, may not mean much, really. Or, it may provide some resonance to how we may be remembered by those who love us – now and later. Maybe in acknowledging the lives of those folks who have gone before us, we see more vividly what they saw. The stitches, music, brushstrokes, or powerful words they spoke vibrating and echoing through us. Perhaps they are not beckoning us home but encouraging us to stay, to use the time we have been given to its fullest. These relatives have made a kind of balm for all of us – like the Quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, who are members of the Souls Grown Deep Collective. “The women,” as they are commonly known, learned to carry forth their generational art of making quilts that now hang in some of the fine art museums around the country, passing the lessons of their brand of quilting to the next generation.

If they were asked, I am certain that “all of our relatives and ancestors” would want us to be whole and happy. They would want us to know that what they made, their art, their writing, their very lives, and ours are all a testament to the fact that they lived and survived to do the work to guide our lives today – if we would only know enough to look up every once and a while to ask.

Curated Viewing

The great stentorian-voice actor James Earl Jones went to join the ancestors this past week. In a scene from the play written with him in mind – “Fences,” see James Earl Jones, with Courtney B. Vance playing his son Cory, from a scene from the original Broadway production HERE.