ANEW: The Collapse and the Comeback

From the heartbreak of ’69 to the search for the opposite of loss

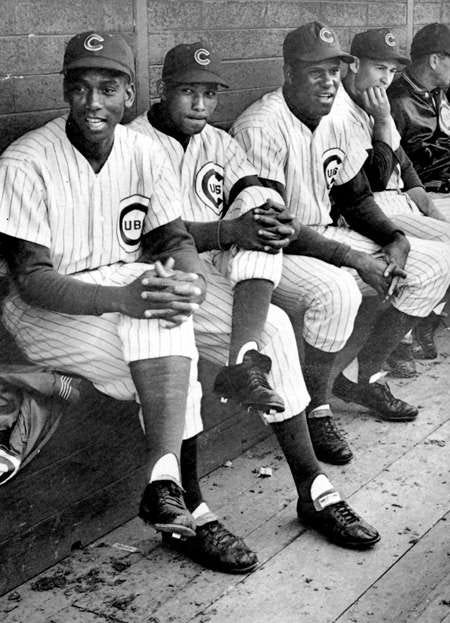

Our dad took us to Cubs games in 1969, the year they looked destined to make a historic run to the World Series, losing out in the final days to the Amazing Mets. For most of the season, they were magic — Ernie Banks, Don Kessinger, Ron Santo, Randy Hundley, Billy Williams, Ferguson Jenkins — names that felt like summer itself. But by September, the magic collapsed. And just like that, the dream was gone.

I think about that kind of collapse sometimes — the kind that seems impossible until it happens. The kind that leaves a mark.

I was no more than six or seven years old then, fresh out of first grade, living in a world where baseball was everything. We played it in the street, scored games in homemade scorecards on Saturdays and Sundays after school, and carried our gloves the way some kids carried lunchboxes. Nothing was better. Nothing was greater.

My mother had been separated from our father for as long as I could remember. I’d never known them together, not really. And yet, somehow, we made a kind of life in sync. We found our rhythm — moving up, moving out, changing grades as easily as some people change lanes on the highway.

Still, the collapse of the ’69 Cubs stayed lodged in my memory. Maybe because it felt like the first time I’d learned that not all stories end the way you hope. Like a first love that lingers too long in your teenage memory — your hands clasped together, palms sweaty, wondering when to let go, wondering if you should at all.

And yet, we had our golden era. Those years felt like they would never fade, our lives perpetually in sync, full of the kind of moments you can only call golden when you look back.

I was too young for Little League. Tee-ball was nowhere to be seen in our small town. Baseball seemed like something the older kids played in an “organized fashion,” with umpires and helmets. We didn’t have the official passport, just a passion for the game that was carried down the line from our father, our Uncle Bob, who had played for the Robbins Eagles, our hometown semi-pro team, and the Birmingham Black Barons, which was the Negro League Team that some of our older relatives still talked about. Baseball was a legacy sport. We also played other sports, such as basketball and football. But baseball was the ticket out if you could hit and run.

Nobody I knew had the gumption or tenacity to persevere through endless summers of sweltering heat and working at hardware stores to make ends meet. Baseball was a hobby at best. A hobby that came with a price, even if you were the greatest player that we had ever seen live — like Ernie Banks. Mr. Cub. #14.

Tomorrow, I’ll go see the Cubs play the St. Louis Cardinals at Busch Stadium. My old team is playing my new team. Now that I live in the LOU, the Cardinals aren’t rivals anymore. They feel more like a reconciliation with a long-lost past—a way of reclaiming something, of trying to stitch together all the versions of who I’ve been.

I’m on the lookout for the opposite of loss. Not the prodigal son, exactly, but something else. Something deeper. Something that doesn’t end.

May it always be so.

Curated Listening:

Okay, I don't know if it was the first, and it certainly won’t be the last, my boyhood team had a fight song that made us all happy — until the collapse. It then became bitter sweet. “Hey Hey Holy Mackerel” (1969 Chicago Cubs fight song) was what we listened to to get ourselves going. If you want to hear a time capsule of my youth, listen to the Chicago Cubs fight song HERE. Better yet, listen to Ernie Banks, a man for years and years I thought looked like my dad, sing the same fight song HERE.