My mom drove around to the back of the school that day. We never usually did that. We lived so close, my brother and I could walk to both buildings—Childs Elementary, which ran from first through fifth grade, and the junior high, which started in sixth and went through eighth before you transferred to high school somewhere else.

The summer sun beat down sideways, like a bass drum. It was the summer between fourth and fifth grade, and the heat had been so relentless you could see a shimmer of false water on the road—a mirage that never materialized because it hadn’t rained in a week. Still, we were on a mission: we were heading to Berniece Childs School to pick up my new trumpet.

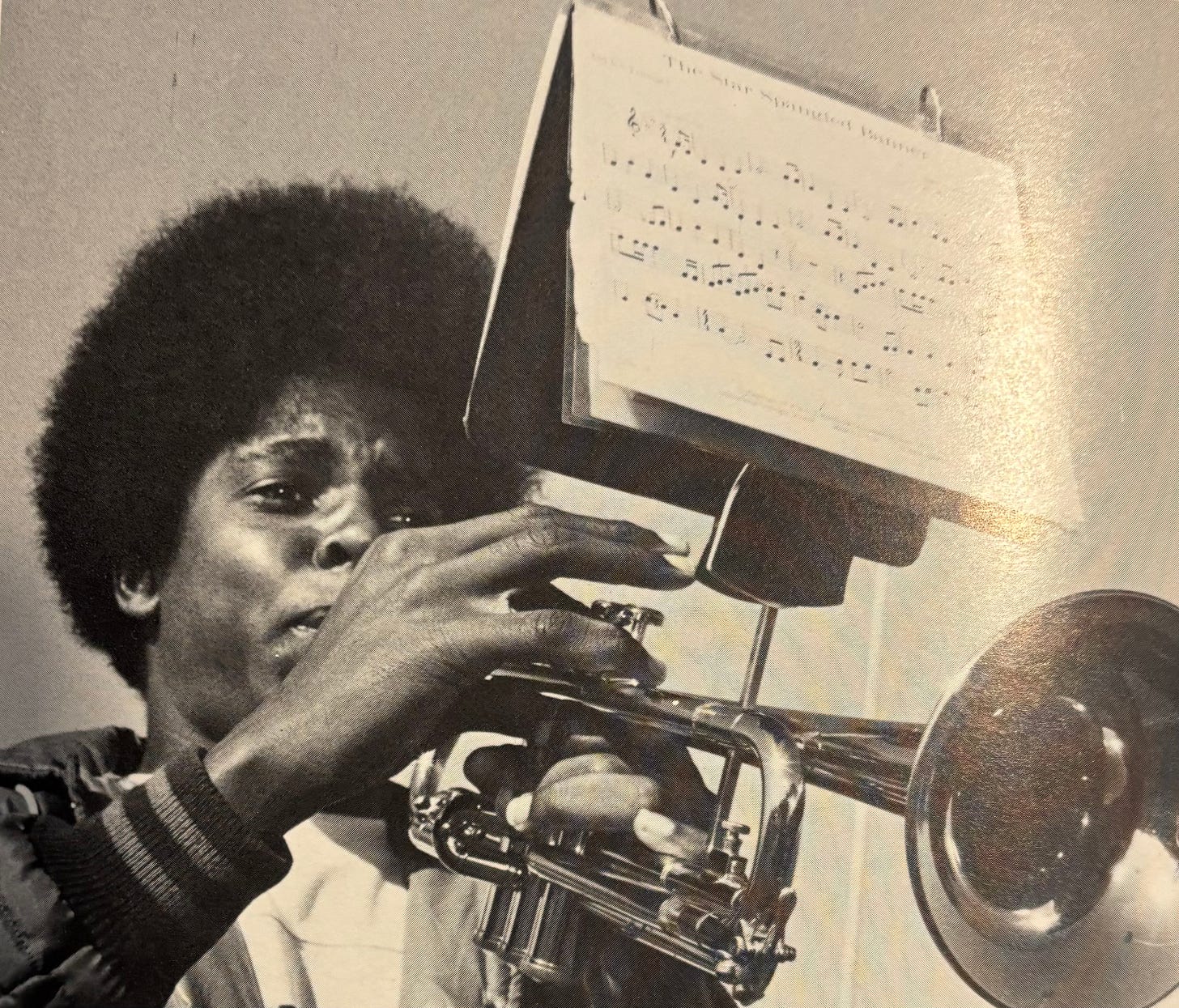

Back then, every kid who wanted to play an instrument could. They gave them away for free. I don’t remember why, but in math class, we filled out little cards saying what instrument we wanted to play. I chose the trumpet. I liked how it looked—bright, bold, and brassy. All I had to do was attend a two-week “learn to play” summer session, and the instrument was mine. No strings attached.

I did the two weeks. I wouldn’t call what I did “playing,” but I got the trumpet.

Then we moved.

It was a new school in a new district, and that’s when I met Mr. Weber.

Mr. John P. Weber. We might have started there the same year. He was the only band director for the whole Harvey K–12 school districts—District 152½ (elementary/junior high) and then moving to the high schools—District 205. He taught concert and jazz band and “served as the concert and jazz band director for 30 years.” During my time, he was a traveling music man, going from school to school each week, giving every student a 30-minute lesson, including me. On Monday nights, he brought us all together for 90 minutes of rehearsal—pulling music and magic from a ragtag crew of kids on the South Side of Chicago.

I only had two weeks of trumpet under my belt, but Mr. Weber never made me feel behind. He didn’t rush. He didn’t shame. He saw what was possible and started from there.

We played everything—TV themes like S.W.A.T., the original Rocky, the kind of songs we loved and begged him to teach us. He usually ended the concert with a song we chose. That meant something to us. It meant he was listening. And that made us want to practice harder—to sound right, to sound real. We also played more traditional band pieces, of course, and his groups consistently won recognition: Mr. Weber’s bands earned “numerous awards… including the Band Excellence award.” But we remember the feeling more than the trophies. We remember how he made us want to play.

Mr. Weber had the patience of Job and the vision of someone who knew what music could do for a kid. As Harvey changed—from mostly white to majority Black and brown—Mr. Weber stayed. He wasn’t just a fixture. He was the heartbeat. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of students passed through his care. There’s a Facebook page now, full of tributes and stories. People writing about how his belief in them changed everything.

I wasn’t part of that later wave of students who had the full Mr. Weber experience. But I saw the beginning. I saw the spark before it became a bonfire.

He had a rich life outside of teaching, too—“a tuba player for the West Point Military Band,” a performer with groups across Europe and the U.S., even a member of the “United Serpents musical group centered in England.” But he always came home to us.

My trumpet—my second, fancier one—is still in storage somewhere. It’s barely played and still shiny. But that first free one? That one got used. That one made me fall in love with music.

High school changed things. If you didn’t play football, you were in marching band, and that came with its own rigor. Our parents—the children of jazz clubs and soul bands—understood band. They understood discipline through music. They understood live sound as life itself. And Mr. Weber helped carry that torch. He gave us access to a language that needed no translation. He gave us an identity through sound.

My brother took it further—drumline, cadences, college band. But he didn’t have Mr. Weber.

That was my blessing.

Mr. Weber gave us music—not just scales and scores, but the confidence to make noise, to be bold, to care enough to practice, to risk playing the wrong note until it became the right one.

“Music was always a big part of John's life,” the obituary says. That’s true. But even more than that, he made music a big part of ours.

And that’s the thing about learning anything well: it takes time. It takes practice. But most of all, it takes someone who believes in you long before you believe in yourself.

For me—and for so many others in that corner of Harvey—it was Mr. Weber.

Curated Listening:

One of the songs we had on repeat in high school—an absolute staple of the American Top 40—was Chuck Mangione’s “Feels So Good.” It climbed all the way to #4 on Casey Kasem’s countdown, and it’s hard to imagine a song like that—a little disco, a little jazz, unmistakably band-driven—getting that kind of mainstream love today. Give “Feels So Good” a listen: HERE.

"He gave us an identity through sound." — Such a lovely tribute to a generous teacher and mentor.

And thanks for the music rec. Listening to "Feels So Good" was a great change up for my Wednesday work sounds!