ANEW: Manchild at Yale: A Novel -- Chapter 9 (a new working title)

Episode #9 -- Formerly B.C.Y.: A Novel (working title)

The new working title of the book is Manchild at Yale: A Novel (working title). I chose this particular title because it aptly describes Schaeffer’s narrative and where he situates himself in the world. It also alludes to two other great works and many of the tremendous post-Great Migration tales, which are innumerable. There are only three chapters left of Manchild at Yale: A Novel (formerly B.C.Y.: A Novel).

One of my two favorite reads as an early teen was Claude Brown’s harrowing memoir called Manchild in the Promiseland, which adds a great deal of emotional resonance and depth to the post-Migration story. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my literary hero, James Baldwin, because his short story, “The Man Child” (in Going to Meet the Man), can also be echoed in Schaeffer’s own life’s resonance. Finally, I am genuinely grateful to Farah Jasmine Griffin, whose work "Who Set You Flowin'?": The African-American Migration Narrative (Race and American Culture), which I admire greatly for her literary dissection and analysis of Black migration literature and music. Griffin’s work — and her new memoir — are just delicious in its clear-eyedness.

Preface: This is a serialization of Manchild at Yale: A Novel (working title). If you missed the earlier Chapters, you can find them here: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8.

Enjoy!

Chapter 9

The summer between my junior and senior years would be my last one at home. I had decided that I wanted to do something completely different than in the years past. Once again, I was placed on academic probation. Getting used to mediocrity. But wasn’t it Voltaire who said, “The mediocre are always at their best.” I would have to take the equivalent of six classes and seven classes, respectively, to pass Yale in my allotted time. I know that there were a number of scars to prove that I had been in the fight, like the three Fs staring me in the puss, but it would take some superhuman strength just to be done. I had a rhythm going, although I needed to continue the “one day better every day” mantra to find my footing. Everything was everything, as the old cats were fond of saying around my crib when I was younger. Everything was everything.

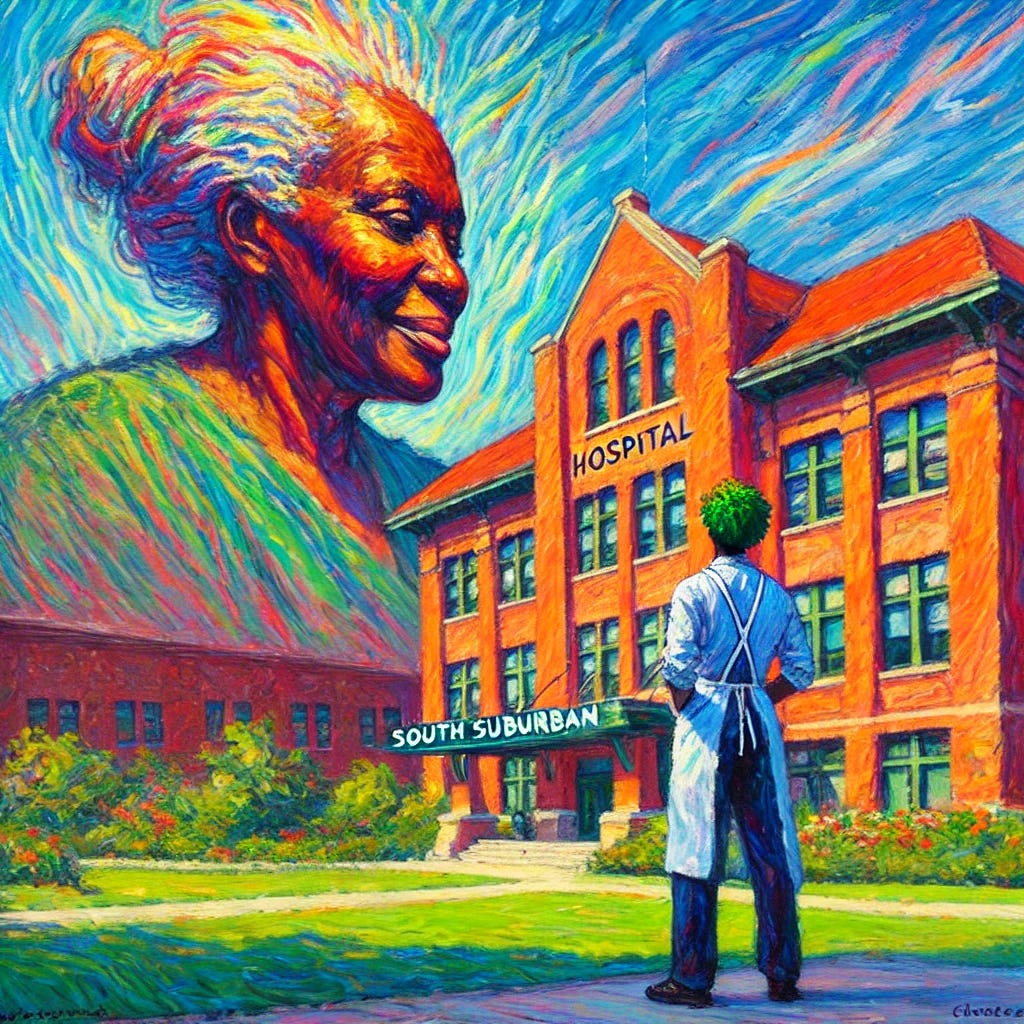

That summer, I said I wanted to work closer to home, so I would apply to our little city’s hospital, as my brother did during his undergraduate summers. He was an orderly. I could see myself doing the same thing. Mylie said the second hardest thing about working in the hospital was having the doctors and nurses at you all day. “Take this down to the blah, blah, blah! Help me lift this bariatric patient. Clean up that colostomy bag spill.” Those docs, nurses, and even CNAs could care less that you were some struggling college student. Mylie knew that medicine was his ticket to getting out of Dodge, and although he majored in radio, TV, and film at Northwestern, he was able to pass all of the pre-med classes that got him into medical school. The people who hired him during those years at Ingalls Hospital appreciated him over the years. Mylie was always the star, which made me kind of the dark star.

OB Nurse: Mylie can you run this down to the lab and bring up the two scrips that’s waiting in the pharmacy?

Mylie: On it! (His white coat and aqua scrubs flapping behind him as he hustled to do his chores)

I would give my right hambone to see somebody ordering my brother around like he did me. It had been at least three or four years since Mylie last orderlied. The image I had was of Jerry Lewis in The Disorderly Orderly, which was not as funny as most of his other movies. Maybe no longer being the funny guy was where I was headed, too. Perhaps heading to the equivalent of post-college land of telethons — or working in obscurity after high school stardom. To help my case for getting hired, maybe they would remember Mylie when I wrote to them and applied for the same kind of position.

Mylie said THE hardest thing about working in the hospital was going to Labor and Delivery and walking the dead babies down to the morgue. They were swaddled in cloth and wrapped like a live baby, but you had to carry them in your arms as if they were alive. That makes sense when you think about it. You wouldn’t carry the bundle like a football or knapsack. I wonder what people said to him as he passed them in the hallway heading to the service elevator. I’m sure the hardened soul that was Mylie had him being extra careful as he took the back-way elevator down to the sub-basement level where the morgue was, checking in with the morgue attendant, giving over a life that was no longer a life.

I wondered how he would even cope with that. What kind of dreams would you have at night if you had to take too many of those babies down every week or even every day? I never asked him. I was the opposite of uncurious, but I didn’t want the idea of dead babies haunting me as I tried to get my own bearings so that I could apply.

Mylie told me to write a good letter, go down personally to the Human Resources Office, and just keep showing up a few times a week until they had to give you a job. To this point, I had had about six jobs in my life—where I got paid—but one didn’t count. I helped the student registration at South Suburban High School two summers before school started. I worked at First National Bank. I worked at Time-Life on two separate occasions—two jobs in two different summers. I worked at the Yale Rep for the run of one show and the Yale Television studio my entire time, which was like a second home for seven hours a week during the school year. I also worked at Marshall Fields for like a day. I quit because I could not see myself being a schlepper of cast-off clothes from around the store. The name of the job was Delivery Boy, I kid you not.

Scanning through all of the ads in the South Suburban Star Tribune and the Chicago Sun-Times, none of them lept out to me as summer only. Just what in the hell was a “Gal Friday” anyway? Anyway, I refused to lie to them as Mylie had suggested to tell them that I would stay beyond my allotted time and into the fall. I didn’t want to create even more bad juju coming at me, although I am certain I wasn’t honest about other things.

The Black lady in the HR department was encouraging at first. She said that there weren’t any current openings at the hospital in something that might suit me, but she would look on my behalf. In my own ethos, I didn’t want to take a job away from someone who had a family and needed a real job, although supporting myself through college was important and noble in and of itself. I went back and forth every two days to check in on my application, but the first week, I had struck out, and I was becoming a pest to the one ally that I had in the HR department, which was the Black lady who said that she would try hard to help me.

If I stayed for an additional four weeks in New Haven, I probably could have made what I needed to make for the entire summer by working the various alumni reunions and cleaning up dorm rooms in New Haven. That seemed about as appealing to me as bloodletting. I knew a bunch of people who worked those clean-up gigs, and they said it wasn’t that bad. Occasionally, they would enter a room of some undergraduate who had stuffed his room floor to ceiling with library books or, like me, had vomited all up on him or herself on the way out of town. I whispered, “I’m sorry,” but was grateful that I wasn’t the only one who left a mess. Working the alumni circuit or staying on at Yale might be a job for another day and time for me, but not this summer. I knew that this summer would be the last one that I got to spend with Mama and Mymama before I left for good. Again, I had no idea what I would do.

Up until this point, I had spent most of my time thinking through just getting through. There was no organizing principle that I had beyond trying to make it from day to day at school. Now, I was pretty clear about this probably being the end for Higher Ed for me at this point. I knew I would not be mayor of Chicago or mayor of South Suburban or mayor of Robbins. I would need to do something different. I was not all that committed to being an actor. After all, I had failed and couldn’t land any lead roles after that. I felt my skills from high school had atrophied to the point that I was like an absolute beginner. The trick that your mind plays on you, however, means that you imagine you can still do and be the gifted artist or athlete that you once were. It was like being some moderately successful athlete making a comeback. Was it a comeback if you never were all that good to begin with? Who would know that it was a comeback? These were the many questions I talked to myself about as I waited for the next week to start to get the job I knew I had to get to make the summer start right.

Again, I showed up at the HR Office at the hospital. Mrs. Ross was there, and she smiled at me as I walked into the office.

“I got some good news for you, Schaeffer,” she beamed brightly. I mirrored a smile back. “The food service department needs a dishwasher and someone to work the line. Also, if you’re lucky, you might be able to take trays up to the floor.”

My face fell. I didn’t know what to say.

“Well, at this point it is customary to thank the person who has done you a good turn.”

“Of course, of course…” I spluttered, not feeling very thankful at all. Dishwasher, I thought. “I do, you know, thank you. Thank you.”

“Okay, I know it’s probably not what you had your heart set on doing this summer, but it is definitely work, and the pay is $8.50 an hour.”

That actually was pretty decent considering what I was making at school and what I had made previously downtown Chicago.

“I was just hoping that I could have a job like my brother had.”

She looked at me evenly but with some tenderness this time. “Those jobs are actually rare and even harder to come by since we have been in a recession. I’m glad that you have your foot in the door here. It might be easier for you to get one of those jobs in future summers, especially if you plan to go on to a career in medicine like your brother.”

I got it. I got it then and there. She had pulled strings to get me a high-paying gig somewhere in the hospital. I was ungrateful, which probably made her feel, ‘Why did I even bother.’ What I would come to realize is I had a long way to go from being exceptional, or rather thinking that I was, to being and working hard because that’s how gratitude was actually demonstrated in the world, or at least in this part of the world that I inhabited. People really didn’t give a shit about your fancy school. They wanted to see you give back in ways that mattered to the wider community, not to just yourself and your family. That’s why those educated folks who went into the ministry and did good work but who came back to work hard in the community they grew up in were so valued and valuable. My ingratitude reverberated in my own head, even only being not a month away from my last encounter with Mrs. Kendrick and the hardship of continuing to shoot my own foot off, toe-by-toe.

I would learn to become grateful. I would humble myself and think about Mrs. Ross every time I washed half-eaten pureed slop down the big disposal on the dishwashing line. In fact, that summer was probably the best one I had in the four years of my time in college. None of them women had much above a college education, or that’s what I thought when I took the job. They knew me because they knew me, and I used to go out with one of the ladies’ daughters. Lydia was the leader of the line, and her daughter and I “went out” in eighth grade. Or, so I told myself. I’m sure it was me getting too obsessive with Justine, and she threw me over for one of my other good friends in middle school. I never quite forgave Justine for that.

“Hey, College boy. You slowing things up down heeeeere.” Lydia sang “here” like she was a cattle auctioneer, voice booming to make sure that people upstairs got their food on time. Chanteal who was the life of the party would be the one to call me out. “Hurry on up, Negro.”

I loved Chanteal the most because she was loud, said whatever she wanted, and had a vested interest in making sure that everybody on her line was successful.

Lydia winked and smiled, “Don’t pay her no nevermind, Schaeffer. She just fussing at you ’cause she want you to be her BOY-friend.”

All the ladies and older men on the line cracked up at the exaggerated way she said “boyfriend” and to think that Chanteal who had to be sixty, if she was a day, was interested in twenty-one year old me. It was funny, and I even laughed at my own expense.

“Schaeffer, she say she gon’ buy you a car. She got the money, don’t she,” another one of my co-workers named Rosalean said. “Um hm, she sure’nough do. ‘Cept, you can’t be running back to college with them old skinny-legged heifers like we know you go with, Ainsley P. Pomeranz the Third, Muffy Delano PinkCheeks, or Gertrude Barbie-kins Guggenheim. Am I right?”

They all laughed, then Chanteal chimed in, “My Schaeffer ain’t like that, is you, Schaeffer? You don’t like them no-hipped skinny-lipped White girls, do you?” Or, ‘do you?’ was like a call to action if I said yes or if I could muster up a convincing ‘no’. So I did the next best thing that I could to preserve my dignity and manhood for the rest of the summer. I said nothing and smiled.

“Okay, I know that Mr. Mona Lisa over here got more to tell than he willin’ to even say, so I guess I’ll let him alone.” All the women ‘uh huhed’ and cackled ‘yes’ in assent at Chanteal summation. I was branded and forgiven for all of my pretensions at the same time.

What I thought would be the toughest part of the job turned out to be the easiest. The grunt work of digging into people’s sloppy seconds, half-eaten melba toast with Postum coffee replacement for heart patients, and wiping away the final remains of the day was comforting somehow. I’d also forgot what it was like to be amongst people who accepted and even loved me for me. Even somebody fullborn and “big-boned-ed,” like Chant-eal. She was well-intentioned and comic relief, but Lydia was something else entirely.

I knew Lydia when I dated her daughter, Justine. That summer I spent a lot of time going around to her house and just hanging out with her and her husband, Major. Justine was finishing up at Northern Illinois. She had a very serious relationship with a fireman at the main station in Harvey. They seemed inseparable.

“Hey, Mama Lydia,” that’s what we called our elders in town, “How you getting along.” I came by at least once or twice a week, often barely rapping on Lydia and Major’s door and setting down a pie that my grandmother had made for Lydia. MyMama was older than Mama Lydia, but they both came from Jackson, Mississippi and grew up around the corner from each other. It was dusk-dark, and Lydia’s house overlooked the long, narrow parking lot on the edge of the now-closed Wyman-Gordon Plant. The Plant loomed large, blocking out the setting sun as the traffic raced by on 147th Street. When Mylie and I were kids, we would skip rocks down the street, trying to miss the oncoming cars. Sometimes, the cars weren’t so lucky. One time, an unlucky guy whose car had been “tagged” screeched on his brakes, backed up suddenly and began to chase us. We ran through the backyards of six homes, three streets, and two alleys to avoid capture or worse. We never played that game again.

With Lydia and Major, I sat and talked about the day at work, or about Justine and her fireman, or what I was studying in college and what interested me. Major just listened quietly, his drink and evening Sun-Times by his side, and nodded off, like so many other Black men after a hard day at the shop or plant. He was just honored to fall asleep listening to the sound of his wife’s voice talking to her many visitors. Lydia, on the other hand, loved the company on the screened-in porch with the ceiling fans that moved the hot air and the volleyballed the indoor mosquitoes around. It was easy to talk to them in a way that I couldn’t talk to my own family.

I’d ask a ton of questions like:

“What was it like to grow up in Jackson?”

“Were the White people really that awful and mean?”

“Why did you all move up to Chicago for?”

“Why do you all go back so much, but other folks just don’t?”

Every night was like twenty questions.

What I learned from Lydia is that the White people weren’t so bad, or that’s at least what I heard at first. You’d just ignore them. Certainly, the folks deep in the country had it much, much worse. Like my grandmother, Lydia worked for a doctor, Homer S. Goodwin. Lydia was friends with Margaret Walker, the writer, and she loved hearing Margaret tell stories. She said most of the women of her generation got married. That’s just what they did. And, some people DO go back and stay, making a life that is good even in the midst of all that they witnessed.

“That’s funny; my grandmother and mother refused to go back down south.”

“That’s on them. It’s just as bad up here in Chicago with these fool Negroes killing each other as it is down in the South. At least we knew where the killer was. It didn’t take no genius to know who to avoid. In fact, we lived decent and separate lives.”

“But what about all the whippings and lynchings and killings by Whites?”

“As a kid, you knew who to avoid. Just like they knew who to avoid too. No-BODY messed with my daddy. No-BODY. There were other Black folks, too. That reign of terror stuff was ridiculous. Some of ‘dem white folks would not mess with certain people and certain families. And I don’t mean the ones that were light-complected kin, either. Things would get bad at times, but they weren’t as bad as having people come shoot ‘chou up in yo’ own house like they did over in Markham the other week. Gang Negroes terrorizing stuff. You expected that from people that ain’t you, but not from people that look like you.”

Since I had left for New Haven, there had been a number of robberies and murders. My godbrother and play cousin ‘Lonzo got stabbed by a rival gang and died with a twelve-inch gash in him. That tore his mother a father up. His father, Big Joe, was a cop, and everything, even being a cop or fireman, didn’t innoculate you from stupid shit. Mama watched the news all the time, and it looked like a shooting range out in the streets. It was helpful to hear that some folks did look out for each other, but I just didn’t understand some things.

Even in high school, but especially now during college, I was trying hard to square what I was seeing in the world and reading in my history books, when we got that far, about what people’s lived experiences were compared to my own. I wanted to know, “If it was so good, why did y’all leave?”

“Now don’t you be puttin’ words in my mouf, here,” she snapped. She flashed a little hot at this. “I didn’t say nothin’ ‘bout down South being good. You hear me, Boy.”

“Yeah. I mean, yes, Ma’am.” Underlining that I was raised right.

“It just wasn’t all bad. I guess that things just get riled up between Blacks and Whites. That’s just a part of it.” She softened thinking about it. “It’s like everybody got to play they part in the story. Some people on the side of good while others, they the bad guy. Then sometime it flip. Sometime it flip where people be actin’ out what they see. See?”

“I guess you right about that.”

“So, what part you gon’ play? You got all that book knowledge, but sometimes the folks with the most learning are the ones that has the most to learn. What kind are you?”

“I’m learning my ass off, but…” I trailed off because I had never put it to anyone before.

“I just don’t quite understand the part I’m playing.” I shrugged. “It’s like I have wandered onto the stage without any lines. Not only that, there ain’t a director or even stage manager in sight. That’s the hard part for me. No direction or me remembering what I should be doin’ and what I should stop doin’.”

She cracked up at that. She laughed like I had never heard anybody laugh before. “You tickle me, boy. You know that.”

“I’m glad that I could make you laugh,” I said darkly.

“Naw, naw, don’t go start pouting like you do on the line when somebody done messed up your row.”

“I just don’t understand why I’m doing all of this…” my voice cracked at the end. I certainly did not mean to put that much emotion into a silly exchange.

“Just play yo’ part, hear? Do the part that was assigned. Like in high school. Nobody was better at playing they part better than you. You here, Schaeffer. No. Body.”

I had a vague understanding of what she meant, but she went on so she wouldn’t have to spell it out. “Play the part that you been givin’. It only takes being the person that yo’ Mama and GrandMama raised to get what I mean. Just don’t do anything to go against that. No knives or guns or sa-diddy, fay-a-weather friends. They raised you right, didn’t they? You don’t need non-a-that-mess, ya’hear?”

I could only shake my head through tears and gurgle out a quiet “‘S, Ma’am.”

“Then just do what THEY taught you to do.”

“That’s the problem, I am listening and trying real hard, probably too hard.” I didn’t want to say that school was too hard. I only wanted her to know that it was sometimes beyond what I could reasonably do. It wasn’t the content. It was the culture. “I just feel like if I don’t…” I trailed off. “I’d be…I’d be…”

“You’d be what? What”

“You know…”

“Letting people down? Is that really what you think, Schaeffer? That people ain’t studying you that much to think that if you don’t get a good grade, or a big house, or one of them gals you probably messin’ with, or heaven forbid, that you drop out of school, that they would care. I hate to break it to you, buddy, but they don’t care. Certainly, there will be people who pretend to care, but in the grand scheme of things, they got too much to worry about to worry ‘bout you! Hear me?!”

“Yes… uh, Ma’am. But I just feel this pressure and…”

“Angxietee,” she pronounced the ‘e’ in a very exaggerated way. “News at 10, boy, they don’t care. They couldn’t give two pieces of fresh dog hockey about your teeny-tiny worries.”

Major snored loudly at this, as if he was agreeing in his dream state, dropping the Times to the floor.

“Just play your part.” She hit each word like it was a drum. “Don’t take on the part of the other fellow. You an actor, right? The act! Would you learn some other fellow’s lines for him?”

I shook my head.

“You damned right. Play your part. Think about what it is you got to do, not what you think everybody back here want you to do. In the end, they gotta pay they own water and gas bill.”

After that, and for the rest of the summer, I did play my part. I was lighter. I had some operating principles to organize my life around.

I spent a lot of time at Lydia and thems house. It was comforting to get re-wound like a clock. It felt like home.

One incident at the hospital solidified my thinking. As the summer wore on, I got to deliver more of the food to the other floors. I ended up in the surgery recovery unit. I saw one of my best friends from high school up on the floor. Ray had been in a horrific accident on I-94, and he was in the roughest of rough shape. I always thought that he didn’t like me much. When I was off my shift, I went back up to see him. He was in a coma. His mother and father, who looked like an older, washed-out version of Ray, were there.

“Ray was so proud of you,” Ray’s mother said. “He felt like you pushed him to be his best self.” She rocked back and forth to soothe herself.

“It means so much to me and Ray that you’re…” she broke off crying. She couldn’t face the reality that Ray was brain-dead and would never recover.

They kept Ray alive for another six months as his already miniscule body shivered and shriveled away to practically nothing. His mom wrote me a nice letter after he died, saying how much that encounter meant to her and Ray.

It wasn’t just the Black folks that were counting on me, but the White folks, too. Play my damned part. Just be. Me.

I decided to once again take the train back to New Haven. It was like a family reunion at Union Station downtown. I wanted to get back a day or two early, so I wouldn’t have to rush. The train ride was calming. I listened to my portable cassette recorder with an earplug. My musical tastes represented an eclectic mix of my roommates and the other people who had influenced me: The Police; Earth, Wind, and Fire; Jackson Brown; The Who; Mott the Hoople; and Luther Vandross. It was a veritable smorgasbord of crazy music from across cultures. It was part boarding school, part New York suitemate, and part WVON-Chicago-R&B Soul. What I was listening to over and over again was Kenny Loggins' “Celebrate Me Home.” I was leaving Chicago but was already nostalgic for my last return at Christmas.

”What do you want from me?” I would say over and over, skipping the “Mama and Daddy” part. Even maudlin and treacle-y pop songs deserved a bit of liberty. Thinking back on getting on the train, my father and stepmother were there. She never came to anything. I later learned that she was not allowed to accompany my father anywhere because he was still desperately in love with my mother. Both women knew it, but my father feigned not knowing it. He just acted as if he were being magnanimous in letting her come.

My grandmother was there, too, pre-stroke. She would be good for a number of years. It’s funny the way memory works sometimes. It is like Judy Garland after she wakes up back on the monochrome Kansas farm. Everything is hazy and full of dust.

Even Mylie decided to take time away from his studies and the frigidity that was his first marriage. He was there looking sad and forlorn. I wanted to tell him to “snap the hell out of it, dammit. This was my damned last going away.”

Finally, Mama was there. She was always there in some form or fashion. Although she did not want me to go away to the wars that was college and life, once I was out, it was ‘come back with my shield or on it’ type stuff. She wanted me to make something of myself in the world, and college would be my ticket.

As I boarded the train, in that sepia-ed time, everyone became locked in amber for me. I was happy for the first time in a very long time. It all started with the hospital, but it was because I was well over the hump of thinking about what would be next. I would cast myself against the wind to see where I would fly next.

Tracing it back to the victory of the past few months, the summer working in the hospital suited me so well. I knew what I wanted to do finally, and I knew what I didn’t want to do. I wanted to work hard these last two semesters, I wanted to find a good-paying gig that could support me as an actor, and I wanted to graduate on time — all in that order. It didn’t matter how brutal my grades would be. I knew I had six, then seven, classes to take. I finally threw away the knife and the memories of the friends and mentors who were not my friends and mentors — and went into the battle, unarmed and unafraid.

But good lord, so much I didn’t know conspired against me. The train ride back was just an interregnum, waiting for some new menace to arise, without even a shield, a knife, or comrades to protect me. Into the breach, again.

[The next Chapter of Manchild at Yale: A Novel (working title) drops on March 21, 2025, in two weeks, which is serialized at ANEW every other Friday. Spread the word and (re-)read from the beginning: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8. Tell a friend. Drink some water. Take your meds. Pet a dog. See you soon.]