ANEW: Manchild at Yale: A Novel -- Chapter 10 (working title)

Episode #10 -- Formerly B.C.Y.: A Novel (working title)

Today marks the beginning of the end of the serialization of Manchild at Yale: A Novel (working title), Formerly B.C.Y.: A Novel. This week and in two weeks are the final two chapters of Manchild at Yale: A Novel.

As I layer on the final touches and edits of the novel, I am reminded of the emotional resonance of doing anything creative, which means putting what you have wrestled with over time out into the world to be received by an audience of people you may not know. For those of you who have read this far, thank you. Remember, you can always jump in wherever you are.

Preface: This is a serialization of Manchild at Yale: A Novel (working title). If you missed the earlier Chapters, you can find them here: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, and Chapter 9.

Enjoy!

Chapter 10

It poured the day I got off the train in New Haven with two suitcases in tow, along with a sundry of other items that my family insisted that I take. Why on earth I would need a waffle iron and one of those ginormous backrests weighing me down, I’ll never know. The rain caught up with us in Western Pennsylvania and stayed the entire time all the way through to Penn Station, then over to Grand Central, and up on the Metro North. What an abysmal time it was to start the end of my college career.

Yet, I remained more of a blank slate, fortified by the sustenance found at home, but this time was different; I wanted to be a blank slate who planned ahead. The planning meant coming to school at least three or four days early, getting settled, and helping the freshmen move in, as had been done for me. However, by the time I arrived, my shoes were holey and sopping wet. I tripped several times as one of the soles of my Salvation Army purchased shoes parted like the Red Sea from the rest of the shoe, as I heeled-toed my way across the faux cobblestones from York Street through the ornate, wrought-iron Pierson Gate. The loud Tower of London sounding slamming could be heard echoing down the walkway, even as I grunted and huffed my way the last leg of the journey. Looking behind me at the distance I traveled to arrive at the exquisitely manicured courtyard and then back up at the Freedom Hall replica, which ominously mocked my way inside, I thought to myself, ‘This is the beginning of the end. Just play your damned part.’

I realized then and there that I had very little upper body strength, with the crap I hauled all the way from home, ditching both the waffle iron and the corduroy backrest just before getting on the train at Grand Central (some homeless dude would be comfortable and sated with waffle-y goodness in Manhattan), and the beginning of trip up to my new room from the Pierson Gate exaggerated that ‘distance traveled’ for me from South Suburban to New Haven this final time.

Coming into the greenery of that courtyard for the first of the last time, examining the well-manicured quad with the perfectly lined topiary, ‘like a bush,’ I thought, as I made my way to our Entryway A living quarters.

Ethan and I made it, is what I reminded myself as I flipped-flopped my way partly across the quad. We had arrived and were placed in a suite with our own rooms and our very own living room all to ourselves. It was a bit more cramped but all ours. I had written to him telling him that I would arrive early on Thursday. He wrote me a cryptic postcard back saying he would get there on Friday or Saturday so that we could “hang out” before the revels started in earnest, but as I carried/dragged the adult human-weighted suitcase up the stairs, I could hear his stereo loudly blaring his music. He was now deep into early ‘70s psychedelia, CSN, and CSNY, which came out of the room, reverberating and redounding down the stairs while having the room itself become its own speaker system that echoed off the walls and into the courtyard, adding to the cacophony of music building in the Pierson Quad.

As I approached the second landing I could hear “Guinnevere” pounding out as I saw that two of the three rooms were overflowing with Ethan’s crap. In one room, which was the slightly larger of the two bedrooms, he had placed two single-sized beds, which looked like a gargantuan king-size bed with a crack in the middle and a single sheet perfectly placed to fill in the gap. Where in the hell did he steal an extra twin bed?!

The only thing I could think of was I wouldn’t be getting much sleep this year either.

“Hey, man. How’s it shakin’ Francis Bacon?”

I turned around slowly after staring at the beds when Ethan came trundling from our unisex bathroom across the hall. “What’s with the two beds, E?” Of course, I knew what he was going to say before he said it.

“Just doing the Boy Scout thing.”

“You mean you need this much room to masturbate?”

“Funny, funny, Mr. Man. I met a girl over the summer who will be spending a lot of time in Bedlam.”

“Really? You’ve even named the suite without me?”

It was like Ethan to pick off some junior or sophomore before school even started. He said they met at a party on the Upper Westside and had been sleeping together at his parent’s apartment ever since. I thought to myself what kind of parent would let their daughter sleep at some random dude’s parents’ place that she hardly knew? That would never, ever happen back in the South Suburbs, at least for no one that I knew.

My quiet, contemplative summer was officially gone. In its place, I felt like I was being displaced as a friend by some chick. My Iago was getting the best of me.

“What college is she in?”

“TD.”

“Year?”

“Why the questions?”

“Year?!”

“Freshman.”

“Damn, dude. Pick on somebody your own age.”

In an Elmer Fudd voice, “Is Schaeff-y-waeff-y jealous?”

“Pissed is more like it. Man, I thought we’d get a little time to settle in before the haunted house howling of the past few years commenced again.” I was angry and I could feel my ears getting hot. Taking a few breaths, “Look, E. I came back early thinking that you wouldn’t be here for a few days so that I could get my head around this final year before another year of coitus began. I just thought I had a few days, that’s all.”

“Okay, so I jumped the gun a bit. My parents are in the Hamptons, and I wanted to see you and her.”

That’s how the year began, navigating the extreme pitfalls of listening to E’s love-making, my own thoughts about what I would do next, and having to carry an overload of classes. It was a burden that I’m sure I would handle but, at the beginning of the school year, I felt my wobbly attention falter. I picked up six classes, as I had to do, and navigated them with some degree of focus. Granted, one class would be devoted to my essay, yet the work had to get done. The reading load was ridiculous, while the writing was worse. My ability to attend was somewhat more acute due to the summer work and hospital discipline, but I still was not back to pre-sophomore year sharpness. During one stretch towards the end of the first month back I had five papers due in a two-week span. I didn’t care. Perfection was not the answer. I powered through stuff I would not remember much about later, which seemed the point of these last four years. Was high school like that, too? Hunting for the toy in the recesses of a box of cereal?

Technology had rapidly changed and we had access to a small bank of computers in a room off of the steam tunnels. I completely dropped the whole idea of anchoring the Pierson Cabaret again, and the thought of auditioning for another play, at Yale or beyond, after all, I was now a “professional ACT - TOR,” was not something I could wrap my mind around, quite. Yet, I simply knew I could not fathom devoting energy to anything else. I had to beat out a rhythm for the new year. My mind was made up at this point. I decided to hunker down that fall. I also made sure that I lived a more hermetic life than I had in all of my four years. One initial paper in Russian History had me flummoxed a little, but I went to see a writing tutor for the first time in my entire career. It was humbling to have to ask for help.

Yet, I was barely able to keep up with the workload. It was like a runaway colt, fleeing a burning barn fire. So much had to be done.

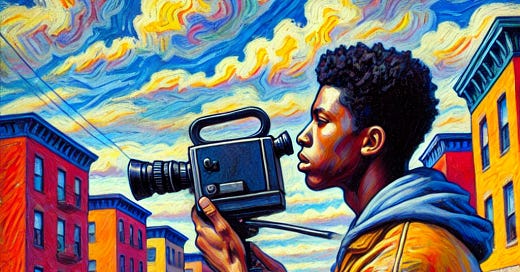

I do not remember a whole lot about many of those classes. It was a lot of do, do, do. The problem with just doing a bunch of stuff is that you do not learn much. My greatest educational engagement came in the Dining Halls, still. I was able to integrate some of the stuff that I was writing and reading, but the learning part was not integrated all that well. I still needed pocket money, so I decided to continue my job at the Yale Television studio. We just delivered more TVs around the campus. I was also able to get into one of the advanced filmmaking courses and a history of cinema class taught by Michael Roemer. That saved me.

Roemer did not tout his own work, but it was amazing to get some of the video tape of some of his earlier stuff and view it between classes or while we waited on a call. He did a film set in the ‘60s with a predominantly Black cast called, “Nothing But A Man.” He also did “Dying” based on Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s work on the five stages of accepting death. That calming effect of making films had me. It hooked me into a creative outlet that I did not have before. At the same time, Alexander Garvin was teaching a seminar about public housing, and I knew I could meld the two things that seemed to give me profound focus.

During high school, I gave up on television and film because that was firmly in Mylie’s territory. He would go on to not only major in it in college, but he also created a bit of a niche for himself before he graduated, doing an internship with one of the local network affiliates in Chicago. TV, film, and medicine were his domains, being on stage and on camera were mine.

Yet, checking out the camera equipment for Roemer’s class and bringing it to the diciest parts of town gave me a passion and an escape while riveting me in a way that I had not received up to this point in my career. All of my classes were still a bit of a struggle. But I was ready for it, even through the loud banging of my roommate and his child bride. The good thing about the roommate situation is that I liked them both. They were sweet with each other. She was older than her years evidenced and he presented as being younger. No matter. We were one big happy suite of people together, but it was all a blur back then.

In Alex Garvin’s class, we took one memorable field trip one Sunday morning in early October to see some of the largest public housing projects in New York City — Queensbridge, Red Hook, and South Jamaica — some of which Alex had helped to work on himself. Alex was a bigger-than-life kind of character with his sartorial bow tie and beautifully tailored suits. He was a vision of what we might one day become.

We were all preps or had become preps during that time. Yale still felt like a White male, blue-blooded men’s college in many respects. There were still carloads of men traveling up to Smith College for mixers, even though women had been a part of Yale for ten years. I must admit I traveled up to Smith a few times, being smitten by a ferociously talented and charismatic woman who was a year younger than I was. It was a very chaste and sweet relationship, even after college. A lot of what I relied on was a kind of Gatsbian version of what relationships ought to be — the stuff I learned in books. It was a lot of like soccer for five-year-olds— kick and chase. Or, should it be kick and chaste?

In Garvin’s class, I got a sense of the ideas that we were wrestling with back at the Better Government Association. The people who put up these housing projects, and eventually the people who imploded them, thought they were doing something good and noble. In the end, they became just more shackles for people, with lots of unwed mothers and kids, because that is what the government required.

That got me thinking: I wanted to explore some of the realness in the Elm Haven Projects in New Haven—both the high-rises and the low-rise units. The low-rise units reminded me of the Cabrini Green Housing Projects in Chicago, or our own home in Robbins, which we called the Old Projects. My mother was nearly shot in the head when she went out the back door in ’68 to empty the garbage. She was caught up in the crossfire between the South Suburban Chicago Disciples gang and the police. She made it back safe inside with a healthy fear that she would hardly relent, not allowing her to exhale until we left the Projects for the confines of South Suburban.

I had a kind of advantage working with Michael Roemer because his film class was housed in a seminar room off of the television studio, and the rest of the class had to come to us for their equipment. I essentially got to assign myself my own gear. I had gone through a couple of rounds of Roemer’s classes, in effect auditing them in my TV studio’s official role, which helped me to complete the projects that the rest of the class would get to do. I was the expert. For the first time, I had some sort of advantage technically and in reality.

The first project would also be something we returned to in the last project that Roemer assigned to all of us, which had to do with motion and creating a narrative arc. That meant we had to choose and plan wisely, which seemed to be the theme of the year so far. He talked about going up to film the people working out on the weights at the Payne Whitney Gym or going to a child’s playground in and around campus. He wanted to see something active, something that involved movement, almost as if we were back in the silent film era.

I remember convincing this friend who belonged to the Carillon Society to let me travel up to the top of Harkness and film what they did. My hope was to get up into the tower and film the carilloners about their work, making music. That idea was dashed at the last minute because the Carillon Society was very protective of their space. They didn’t want some idiot with a camera climbing up to the top of Harkness Tower and falling to his death. It would be on their conscious. Harkness had been covered up for most of the time we were in school. Senior year was the first time I recall that the newly cleaned and scrubbed Harkness Tower was unveiled for all of us to enjoy at the start of the school year after years of putting the scaffolding equivalent of a “condom” on it.

I switched gears fast and decided to travel up Dixwell Avenue instead. That made all of the difference in the world for me. I decided to do a short documentary with motion and broaden it out eventually to editing inside of the camera that would be a great case study, mixing a lot of my interests, I surmised.

There were some graduate students living in the Black part of town, but very few undergraduates would go beyond Payne Whitney. Over the course of the entire term, I familiarized myself with the people and the neighborhood before I even took my camera out. It was pretty obvious that I was from Yale with my weird Izod-knock-off-factory-seconds shirt (thank you once again, Ethan), but I hadn’t been too far-gone from my own neighborhood to not understand what it was like to be from “the neighborhood.” I did have memories from freshman year, being chased back to campus during the first snow. That seemed like a million miles ago, those years.

I had a ritual of going through the camera and working to make sure that all parts and pieces were in working order, including the battery and having enough video tape so I wouldn’t get stuck out in the middle of Dixwell without any footage. I became obsessed with it.

For my first time, I prepped a series of questions before I went out that after reading it over several times looked like it was written by a third-grader:

What’s your name?

How long have you lived here?

What’s it like to live here?

What could be done to improve being here?

If you could live anywhere besides here, where would it be? Why?

After looking at my starter questions, I was sort of ashamed. They weren’t just childish. I wouldn’t insult children in that way; they were so schlocky and amateurish. Stock. They were the barebone notes from a Black Yale student who had spent far too much time away from Black people.

The stuff that we saw growing up should at least let me talk to some people with a sense of realness and honesty that I couldn’t muster with some of the pathetic questions. I’d want to shoot it more cinéma vérité style. These interviews would build upon each other over time.

Lugging my boxy gear past the latest and newest fancy restaurant at the corner of York and Elm, up Broadway in front of the Co-op, beyond the boundary that was Yale, and into the Dixwell projects. The red-brick low-rises were on my left walking north while the high-rises were a blight on the right. I carried the suitcase with my camera along, hoping to get what I came for, which was a decent interview. There were boarded-up windows on both the low-rise and high-rise buildings, but the taller buildings just looked like something out of the Robert Taylor homes in Chicago. Alex Garvin had taken us to some government buildings that stood the wear, tear, and test of time in Queens. Yet, we could have just as easily been in Chi-town or the Bronx or St. Louis or anyplace where the government and some of its residents stopped giving a good goddamn about the inevitable decay without a plan to keep things evergreen. I tried to shoot early in the day when the light was good. Overcast days were the best for what I needed. I would be shooting on grainy videotape that was back and white. It would feel like the sixties or something from way back.

Each time, I scouted around looking for people who might be amenable to talking to me about my project. I saw one woman on my first day of shooting who looked like she wasn’t in a hurry to be somewhere or go to work. Would it always be like this?

“I’m doing a video on Elm Haven. Do you got time to talk?” I went into my best code-switching, but I knew that my speech and debate training would belie me.

“No thank you.”

“I’m a student, and I was..”

“I said, no thank you.”

I approached a guy probably a little older than me and asked him if he wanted to be on camera. At first, he agreed, but then he said he had to hustle on over to catch his bus on Whalley Avenue, “Maybe later, Blood.”

Then after weeks and weeks of trying, I found her, La’Nita. La’Nita was a dream come true. She was the person that I used to “wrap the film, meaning that she would be the opening and closing of some of the segments that I would use to talk about the vitality of the community, the strength and hardship that people would have to endure, and what went wrong with the Elm Haven. You could tell just by looking at the Projects that something was not quite right.

“Okay, I thank you so much for…for agreeing to be on camera, La’Nita. I appreciate it and you. What I’m goin’ to do is ask you a series of questions about where you live. You do live in the projects, right?”

“Yea-ah, I told you Yea-ah. I live in them low-rises over there.”

“Okay, okay, just save it for the camera. Let me get it ready and rolling…state your name.” I squinted through the viewfinder.

“Uh, okay. My name La’Nita. La’Nita Riley. I live right over there in them buildings, or them group of buildings right there.”

“How long have you been living here.”

“I was born down in North Car’lina, but here, I been here since I was four. Four or five. I don’t know. I was too little.”

“Why’d your family move up from down South?”

“We had fam’ly up here. My Uncle Ant’ny and his kids. My daddy also wanted a better job. Him and Uncle A. grew up down there on a farm, Tobacco Road. They was on this tobacco plantation. My dad, he picked cotton, too. He came up to give us schooling and a better life.”

“And what happened?” I had to remember just to have a bunch of open-ended questions so that I could hopefully edit it over some of the shots that I would get over the weeks and months, shots of Black folks moving working, living, and interacting with each other down Dixwell and in the projects.

“Hey, what you gon’ be using this for?”

“It’s just a project. A project for my class.”

“You go to Quinnipiac? My brother went there for ‘bout six months. He ran out of money.”

“No, I go…I go to..uh...Yale.”

“Damned, whyn’t you say that in the first place.”

Camera still rolling, “I didn’t think you’d talk to me, actually. Sometimes people don’t.”

“I. Wouldn’t. Talk. To. You?”

“Yeah, I mean you know…”

“Nope, but you gon’ tell me though.”

“See, I grew up in the projects in Chicago…or right outside. They were just like the low-rises.”

“So what, you slummin’ now. Trying to pick up girls, is that it?”

I couldn’t tell if she was pissed off or…

“I’m just breakin’ your balls, man. Don’t nobody care where you from.” She laughed hard at this. She got me good.

I exhaled long and hard, flashing back to one of my many conversations last summer with Lydia.

She winked at me when she said, “I gi’ you what you want. This for a project? For a class?”

“Yes, Ma’am.”

“Don’t be ‘yes, ma’aming’ me. I ain’t much older than you is.”

“Okay, you ready?” At that point, she launched into a heartfelt and cogent discussion about the projects. The people that she knew. She talked about the City and police neglecting the projects, both high and low-rises. How you couldn’t get an ambulance to travel through Dixwell after a certain time of day. She said that people still tried to take care of each other the best they could. There was a community garden around the back of one of the low-rise buildings. People shared vegetables and stories with each other. That’s what she said that she loved the most about where she lived. She loved listening to the stories of the people who were still here and some of them who left, and some of them who died. She loved those stories.

“Can you tell me one that you really liked?” I asked.

“I don’t know ‘bout like, but there was this family who lived kitty-corner to where me and my mother, father, sisters, and brothers lived. Like my family, there were five of them kids, too. They oldest brother was older than my oldest sister. I ‘member the girls ‘round my age or a little older bein’ real smart and proper. They oldest sister, especially. They mother worked down at the phone company, SNETCO, while they dad worked over for the City. He worked in the sewers. I ‘member they was a very handsome couple.”

She stopped for a moment to collect herself because you could tell this really meant something to her. I zoomed in slowly until I could see her eyes as they began to well with tears.

“They were really beautiful. He had dark, dark velvety-skin, you know, like an African. She was pretty fair, kinda caramel-color-complected. When people saw them…” She stopped for a moment to choke back tears. “They was some pretty people, people would say. They some pretty-ass Black people.”

I kept the video rolling, but I began thinking about my own ‘pretty’ mother and father, tearing up a bit myself in her recalling what she was about to reveal.

“So, one day…” she inhales and exhales real hard, “He goes off to work and she goes off to work. I used to babysit they younger kids. I was older than the little ones, so I would sit with them and play with them. That’s the way we do. Even though they had enough brothers and sisters, we was, like all mixed in together like that with them. The youngest girl, Zena, she had such pretty hair, and a gorgeous smile, even with her two front teeth missing. She was a pretty dark-skinn-ded Black girl. By 2 pm, these men, White men, in big jumpsuits come by. They all black in the face, just like they was coming from one of them old-timey minstrel shows.”

She looked away, and I looked down to the side of the camera to see that I didn’t have much tape left; it was the end of the reel. I couldn’t believe I was running out of videotape.

“They asked me, real serious-like, did they know the people that lived over there. The men pointed to the kids’ house. I knew at that point. I knew something had happened to her or to him.”

“Stop! Just stop for a moment. Hold it, please.” I fumbled in my bag. I kept the extra tapes in a plastic shopping bag from Wawa’s. Hands and fingers not quite working. “Just hold it. Just hold it.”

I threaded the tape through the camera, but it was too late. The moment had passed. I missed the moment. She went through the rest of the story. How the father died. He was trapped underneath the street, methane gas overtook him and three other men that he was working with that day. It was so tragic. It was so tragic, she said, that the story of that day even made it onto the Walter Cronkite news program.

I felt horrible because I had lost the emotional thread of that moment. It was gone. She described the story’s end, matter-of-factly, but it didn’t have the power that the first part of the story had.

Again, I failed, another big fat F in my eyes. Of course, I shot the other footage and some of the other residents who told me about their experiences. The two-minute reel at the beginning of the term ballooned to something more substantial by the end of the course. They gave me some good and some not-so-good stories. What I realized is that I just didn’t have enough time to do all of these stories justice. Who was going to tell these stories? Who was going to record them? That was the real question.

In the end, I felt like I just could not do anything right. I tried to hold onto that emotional throughline that I had when I left home. It was all of the stuff that I packed in my suitcase, that my mother made me take with me, my suit of light to protect me against what she knew was coming. The emotional stuff that was really down in the belly of the bus. All I had to do was show up, but I had a hard time showing up. I had a hard time sometimes even getting out of bed.

That was the real tragedy of the Elm Haven Projects piece in my mind. I wanted to show something, to prove something to the world that had never been seen before. What I gave was more of the same.

When I showed the film to Michael and the class, they cried. They couldn’t believe the strength of the people or the places that were just beyond their ivy-covered walls past Payne Whitney Gym.

I was confused. I knew what it was supposed to be and what it was supposed to sound like. I missed my opportunity. Again, I just botched it.

They read that disappointment on my face when I said, “I tried, you know…”

“No, no, that isn’t true. That isn’t true at all,” I heard Michael Roemer say in his German lilt with the soft “Ls” and the rolling “Rs.” This is good. This is very good. Indeed.”

That was the final class on the final day of the semester.

Ethan and his girlfriend broke up again – for a short time. I dated her for a minute during reading week. Perhaps “dated” was not the right term. He was pissed at me. We had a fistfight across that big double twin bed. We were friends still — in the end.

The end.

I left for the winter break for the final push. The final assault on this series of assaults. My own vision was too cloudy to be true. Even more dejected in myself, I felt, like I couldn’t really do anything right.

I ended up with the best grades that I had ever gotten while at school. I know I did. But I never checked. I was just ready for it to be over. Finally.

[The final Chapter of Manchild at Yale: A Novel (working title), Chapter 11, drops on April 4, 2025, in two weeks, which is the last serialized chapter on ANEW. Spread the word and (re-)read from the beginning: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, and Chapter 9. Tell a friend. Drink some water. Take your meds. Pet a dog. See you soon.]